Will Federal Funding cuts hit Colorado’s Fourteeners?

Much of the discussion around budget cuts and layoffs has focused on the National Park Service. But the Centennial State’s most popular peaks are maintained by another organization.

Recent firings and funding cuts have led to protests, and panic about the future of our natural resources. While these changes are happening at the federal level, you may be wondering whether your favorite local gems could be impacted.

In the Colorado Rockies, the Fourteeners immediately jump to mind. This collection of 14 thousand foot-plus peaks can rival the busiest national parks for visitor numbers. But who takes care of them? And are they safe from spending cuts?

The answer is a vague and slightly ominous one: for now… but for how long?

Before getting to the finances, it’s important to know a bit about the organization that actually does the work, why it’s so crucial, and the challenges they face.

Meet the Colorado Fourteeners Initiative

…or CFI for short, handles the difficult task of building and improving trail infrastructure on some of Colorado’s most crowded hiking destinations.

On the overwhelming majority of these peaks, trail routes were unplanned bushwhacks — usually cut straight between the closest road to the summit, or following the bones of disused mining claim roads.

Because of this, CFI inherited a litany of problems the mountains’ first ascenders never could have foreseen, including by way of example:

Nonsensically steep and washout-prone trails (Elbert via Black Cloud)

Private property penning in tiny trailhead lots (Grays & Torreys via Steven’s Gulch)

Access & liability concerns stemming from mining claims (E.g. Bross, Lindsey)

Put another way: the group’s work is far beyond a cosmetic nicety or quality-of-life upgrade for visitors. CFI’s trail upgrades can actually offset the environmental impact of tens of thousands of visitors, putting the organization’s work firmly in the class of conservation.

Quandary Magazine explores this topic in much greater detail in our 2022 documentary, “The Alpine Amusement Park,” if you’re looking for a deep-dive.

Picking up the Tab

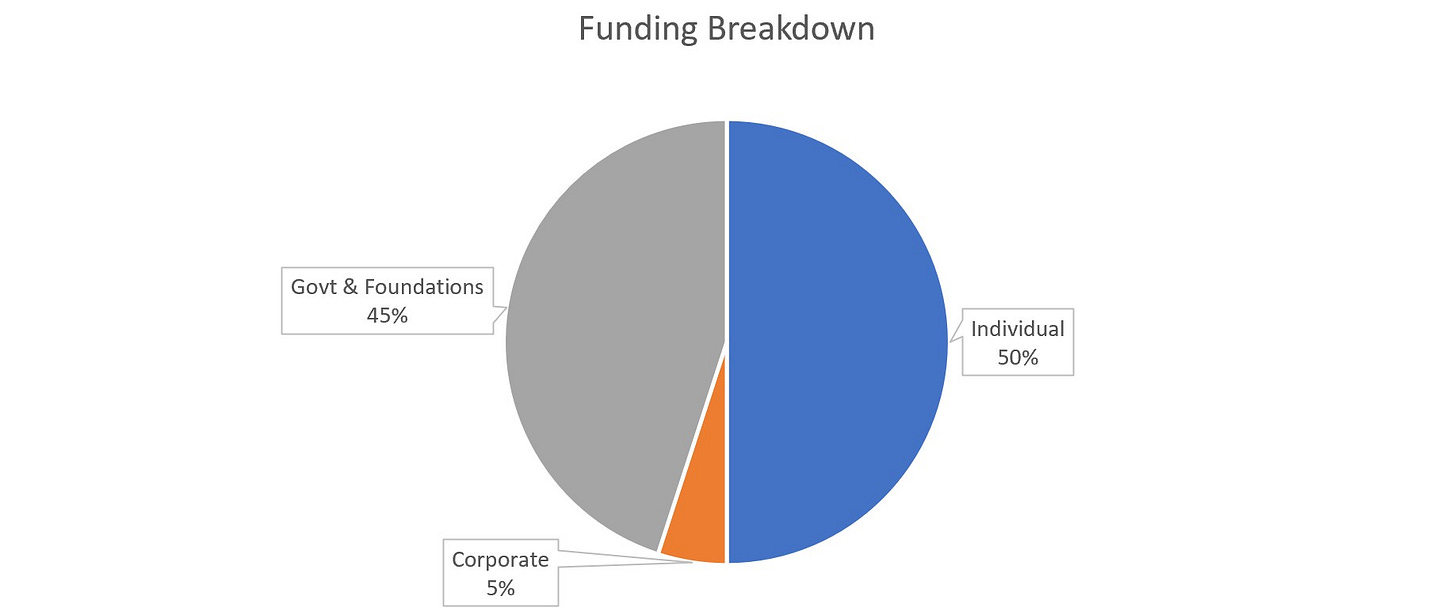

A significant chunk of that work is financed through individual donors. CFI Executive Director Lloyd Athearn ballparked the split for a typical year, during an interview with Quandary Magazine:

“Let's say, 50% is from individuals, 5% is from corporate, and then 45% is split between government and foundations, and it can do all sorts of quirks can slide from weighted to government or weighted the foundations in a given year.”

Of course, CFI doesn’t just get a check from “The Government.” The money flows through quite the array of middlemen before being spent on gabions and trail re-routing on your favorite mountain.

The U.S. Forest Service is a big one, which pays CFI through Challenge Cost Share Agreements — generally, one for each forest. First authorized in 1992, these essentially let the USFS pay third parties to carry out projects that “enhance forest service activities,” so long as they meet a few requirements, mainly:

Improvements must be on federal land

The third party (CFI) has to match at least 20% of the cost

Reimbursement is based on actual cost, not value

No advance payments are allowed

That last point means CFI has to put up all the money, and doesn’t see a cent until after the work is done. And that’s not unique.

“With specific projects, especially those funded by GAOA (Great American Outdoors Act,) there can be more money transferring from the feds to us. When they do that, it's all based on sort of a reimbursement basis,” Athearn said.

“And there is a grant through the Great American Outdoors Act, which curiously was created by Trump and former Colorado Senator Cory Gardner. So it's curious that that is potentially at risk, since it was something that came about in the first Trump administration.”

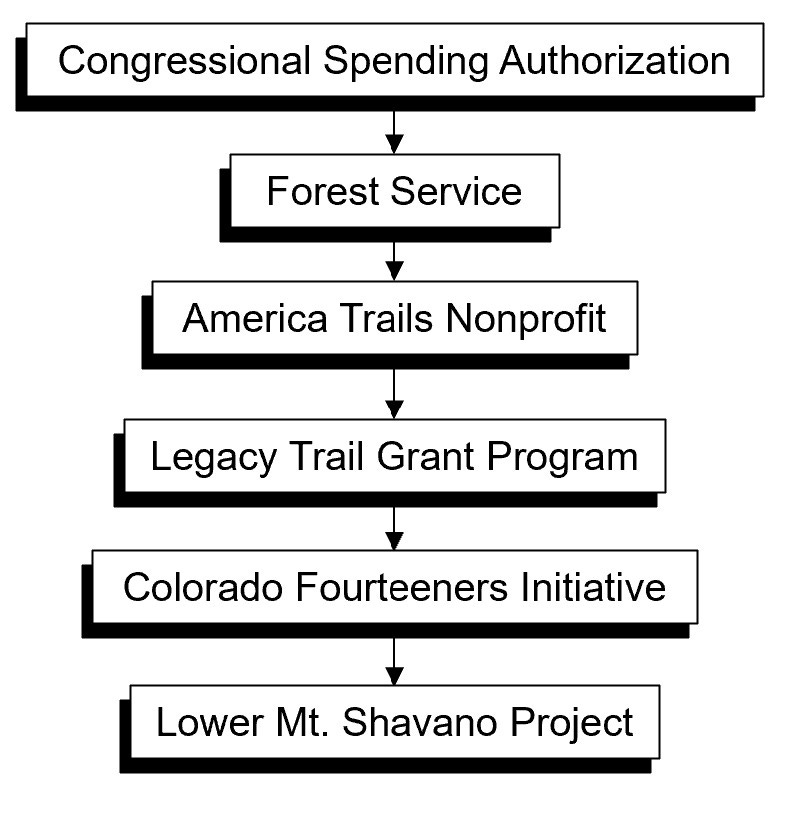

Other money can filter down through longer chains of more traditional grants — though the original payor is still the federal government. Athearn gave this example of how $42,000 made its way through the system and onto the trails:

The multi-year Mount Shavano project in question is also largely supported by funding from the Great American Outdoors Act.

“The funding for some of our crew members there is coming through the state, but from federal money. So if there's a cascading lack of confidence in federal money, that project is the one that would have the greatest risks associated with it,” Athearn explained.

Right now, there’s no indication CFI’s funding is in jeopardy. Grants have been written to cover the organization’s work — at least through 2025 — with congressionally authorized funding. However, this would not be the first time the Trump administration has clawed back money that had already been dispensed.

“It's as if we're dealing with some sort of, you know, bankrupt company that's just saying, ‘oh we're out of business, sorry we can't pay what we pledged,’” Athearn said.

Granted, one of the core arguments behind the ongoing efficiency push is that the United States pretty much is bankrupt, and at risk of collapse without some serious spending cuts. Even if you subscribe to that argument, it’s of little comfort to the organizations who depend on that money.

Strengthening Support

Currently there are no pending policies at the federal level that directly impact CFI, though it remains to be seen whether that changes in the future.

However, you can still get involved by making a contribution to their work. Remember: the largest share of money flowing into the organization comes from individual donations.

Quandary Magazine profiled CFI during our special “Colorado Gives” episode of the Trail Talk podcast a few years ago. You can hear more from Executive Director Athearn about how your money makes a difference.

Quandary Magazine will continue to monitor for funding developments. If you’re concerned about preserving Colorado’s 14ers, share this article on your social media site of choice.